Issues in the education of girls in India

John Gore, Education Consultant, Australia (Paper given at the 2013 Pacific Circle Consortium Conference, Honolulu, Hawai’i)

High media profile events in India involving the rape of a woman on a bus (December 2012) and of children as young as five (The Hindu 22 April 2013) have caused worldwide alarm and thrown a spotlight onto the status of women in India. The reports of women and girls being raped in all sorts of circumstances in India have galvanised not only many Indians to protest about the treatment of women, but a human rights voice has been resounding from around the world.

Most Indian women living in cities and who travel alone on public transport would claim some experience of sexual harassment. In rural India, caste hierarchies still continue and Dalit (“crushed” people formally known as “Untouchables”) and Backward Caste women and girls are often the subject of sexual harassment, including rape, by usually higher caste perpetrators who often act with impunity.

India is a country with laws to deal with these situations, but enforcement is an issue. That women are now doing something about such matters is an indictment of the lack of interest by those in power and those who police justice.

The attitudes to women and their status, as displayed in these events, lie deep within Indian history, cultural and religious traditions, its exposure to western culture and in beliefs about human nature and evil in the world. However, understanding these causes is merely a prerequisite for change and the education of girls holds more hope for a long term change in the status of women in India, one that will embrace respect and true equality.

Cultural factors

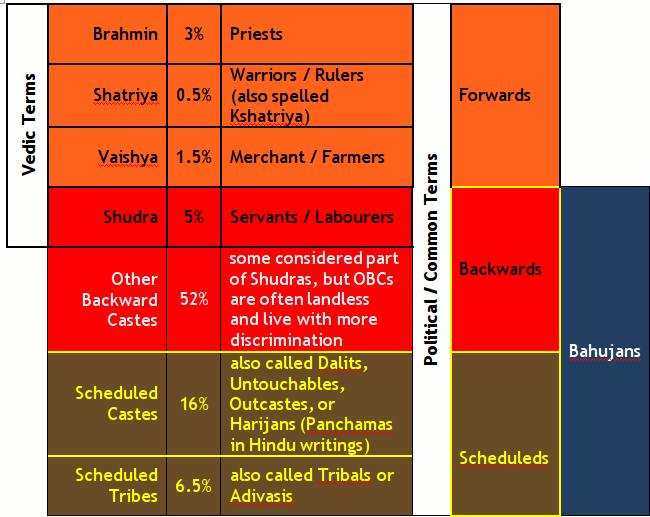

One factor affecting the status of women is the historic treatment of women through the invaders and occupiers of the Indian sub-continent but more pervasive is the Hindu caste system, which has existed in India for more than 3,000 years, and has four distinct groups. The Brahmins are the highest and are the priests and arbiters of what is right and wrong in matters of religion and society. Below them are the Kshatriyas, who served traditionally as soldiers and administrators. The Vaisyas are the artisan and commercial class, while the Sudras are the farmers and the peasants. Beneath the four main castes and outside the system is a fifth group, the Scheduled Castes (SC) known as Dalits. Scheduled means they are listed in a special “index" appended to the Constitution.

The Dalits generally perform the most menial and degrading jobs including dealing with the bodies of dead animals or unclaimed dead humans, tanning leather, from such dead animals, and manufacturing leather goods, and cleaning up the human and animal waste. Caste rules hold that Dalits pollute higher caste people with their presence.1

As indicated in the following diagram the majority of Indians are in the lowest castes and below.

These religious and societal beliefs related to caste, place people of both sexes at a social disadvantage, but especially women who are discriminated against in every caste. The entrenchment of caste is so great that only marginal change has occurred in the past twenty years in Indian cities amongst a growing middle class. Rural India remains a place where women are generally not respected in any caste and are at the mercy of those with power and position.

The missing girls

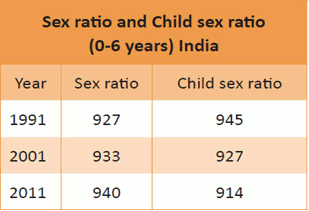

For many girls being born is just difficult enough. The 2011 census confirmed an improved sex ratio for women with them living longer, but it delivered bad news on the sex ratio of children for 0-6.

For every 1,000 boys under six years of age there are only 914 girls. The ratio has worsened with considerable variation across the states. Haryana has 830 female children and Punjab 846.2

Abortion and infanticide are worse today in India then ever before. The inherent desire for a male child places female foetuses and babies at great risk. Although against the law to reveal the sex of a baby, the cultural norm of ignoring the law sees such practices as carrying an ultrasound on the back of a truck to villages where for a few rupees all is revealed. It is not the law that will save female foetuses and babies but a change of mindset.

There are estimates of up to 50 million missing women from the population statistics of India due to abortion, child murder and the greater death rates amongst female children supported by the statistics for operations and referrals to doctors being significantly lower for girls than boys.

Why are female children unwanted? Indian families rely on their sons and daughter-in-laws to keep them in their old age which in India can be from the mid fifties. For poor families this is a matter of great concern. For rich families there is less pressure for boy children although they are preferred.

When parents have a girl child they know that she will leave the family to be married, often in her early teens, and become part of another family. This marriage will require a gift (no longer called a dowry because it is illegal). She will contribute nothing to household income and be a drain on the resources of the family. Why would parents educate her, just so some other family can have whatever benefits that education brings? And what if that female child has a disability and is unlikely to marry. For many Indian families the birth of a girl child brings despair not joy.

Education of girls

As reported in Government stalling secondary school reforms (Deepa 2008), information and figures for all of India indicate that:

- enrolment and retention of girls in city schools is much higher than rural schools

- some schools purge their Year 9 classes to ensure that the Year 10 results for the school are high

- only one percent of Schedule Tribal (ST) women in some states finish high school

- that 25% of schools are private schools (including Roman Catholic) catering almost entirely for the privileged sections of society

- in some states the curriculum after 7th Standard is set at a high standard to suit the students who will succeed at university, thus further discriminating against students from SC and ST backgrounds

- the testing programs in states favour rote learning and not understanding

- that teaching is geared to rote learning of state supplied textbooks

- that distance to secondary schools in rural areas remains a problem

- some private schools exist in name only

It is not surprising that each student succeeding at 10th Standard has a reason to celebrate. That few of these children are SC and ST students is not surprising and in some states primary drop-out has been increasing.3

Retention is a huge problem as illustrated by some statistics4 for Andhra Pradesh which in terms of education, population and size is right in the middle of any state league table. There are as many states better as there are worse than Andhra Pradesh. In this state 15% of children never go to school. Of the ones who enrol the dropout rate by the end of 10th Grade is 62% and for Dalits 72% and for Tribals 84%. At the end of 10th Grade examinations the pass rate is 52%. This means that 13% of the children in the state of Andhra Pradesh can attempt to proceed to college, Grades 11 and 12.

Nationally the enrolment and retention of girls is lower than boys by between 4-18% further limiting the opportunities for girls, with ST girls facing the most difficult pathways. (Sarma 2008). These figures mask a more depressing situation for Northern India. In Southern India the number of girls in secondary school is not far behind the number of boys but as illustrated in this newspaper article the situation in the north for girls in secondary schools is alarming. Although education is considered the most essential tool to empower girls and women, people in Jharkhand seem to underestimate its importance. As per the latest data provided by the government of India statistics of school education 2007-08, out of approximately 6.5 lakh (one lakh is 100,000)) girls in the state only 1.7 lakh girls (26%) are enrolled into the secondary level of education.5

It is not uncommon to visit private schools in northern India and find just a few girls, if any, in Grades 9 and 10. The drop-out of girls accelerates after 5th Grade and continues unabated till there are just a few girls left in 10th Grade. While some are moved from private schools to government schools because of lower costs most simply leave school. The girls most disadvantaged are Dalits, tribals and those from Backward Castes – the majority of the population. Getting these students to school, keeping them there and having them graduate at Grade10 level are all huge tasks for education providers. Across India girls are not always educated and many have minimal understandings of their own rights. Estimates show that for every 100 girls in rural India, only 1 reaches class 12. (Educategirls 2013)

Many of the factors causing dropout are well-known and well-established: cultural reasons such as the belief within the family that girls do not need education as they will not work outside the home; a worry about adolescent girls spending time outside the home and girls marrying early; it may be a cost-related decision where, for example, a family will choose to send a son rather than a daughter to school, and she would be expected to help out at home instead.

Other reasons for dropping out are external and could arguably be dealt with through better provision of education facilities. For instance, while primary schools are often situated close to residential areas, rich and poor, secondary schools are fewer in number and are often located further away, leaving parents worrying about the safety of girls on their way to and from school. Likewise, there are security concerns at school with girls at times facing harassment from both male students and teachers. Lastly, a major issue is the lack of separate toilets for girls in schools: in fact, 36% of schools do not have a separate toilet for girls, and that number does not include sanitary facilities that may exist but are out of order. (Stone 2012)

In one study (Mohanraj 2010) in Madhya Pradesh it was concluded that: The social positioning of girls and women, the perceived future role of girls as mothers and home-makers, the patri-local marriage system, community pressure and the usefulness of girls at home have detrimental consequences for girls‟ education.

Policy options, among others, include – elimination of poverty, improvement of school infrastructures, increased numbers of trained teachers, and adaptation of the curriculum to the present needs. (Basumatary 2012)

The importance of educating girls

Already some states like Tamil Nadu have embraced progressive policies that have girls attending school and graduating in the same numbers as boys, but these states are the exception. The reality for most Indian girls is a long hard road to get equality of opportunity, especially in education. The evidence is that educating girls leads to higher productivity in the economy, higher earning potential and lower maternal and early child health problems. Despite the clear societal advantage of educating girls beyond primary school, there are few private or public secondary school initiatives to promote girls’ education. (Stone 2012)

Educated girls have the unique ability to bring unprecedented social and economic changes to their families and communities: reducing birth rates and child mortality, improving family health, reducing political extremism and violence against women and increasing both family and national income. Additionally, educating girls accelerates overall literacy: mothers with a primary school education are five times more likely to send their children to school. (Educategirls 2013)

Making a difference

Indian governments, national and state, recognise many of these advantages and problems and want to provide education for all students to at least Grade 8.2 Recent (2009) national legislation for compulsory education to Grade 8 has been enacted and faces enormous implementation and resource issues - school buildings, trained teachers and government intent. After three years Statistics show that a shortage of 12 lakh teachers in primary schools, 20 per cent of the teachers employed are untrained, and the student-teacher ratio falls short of the prescribed norms. (The Hindu Even after three years, RTE fails to deliver 1 April 2013)

Community perceptions of government schools paint a depressing picture of the standard of education, the dedication of teachers and the success of girls. The Government has required non-government schools to take 25% enrolments of students from Backward Castes and Dalit and tribal backgrounds. However, legislation is unlikely to help as many of these schools talk about complying, if necessary, by having these students separated and taught in isolation from the rest of the school.

In addition, a growing non-government school sector is cashing in on community distrust of government schools and on the enormous desire of parents to have their children educated in private schools, by creating a range of high and low fee private schools that are reaching beyond the growing middle class. Some of these schools are targeting directly the Dalits in the slums of cities and in poor remote rural villages and accessing considerable overseas funding to resource these schools. One such organisation is Operation Mercy India Foundation (OMIF).

Raising the status of women will be accelerated most by raising the status of the Backward Castes, Dalit and tribal women. Their numbers are politically significant and as seen recently in the demonstrations against rape, women can force change. The education of these girls is of fundamental importance to the future of India.

Educating girls from disadvantaged backgrounds

In the front of the students’ textbooks in Andhra Pradesh is written Untouchability is a sin. Untouchability is irrational. Untouchability is a crime. Untouchability is anti-national. Then why does it continue?

Hinduism in its many forms remains the dominant religion of India and most of its priests continue to teach about and uphold caste and therefore by implication untouchability. People are born into their caste or into untouchability because of the bad or good karma of their previous life. If they manage to live a good life and please their gods during this life then they will be born into a higher caste. So people deserve the caste they are born into and they can not expect to change it in this life. But it is not only within Hinduism that caste discrimination prevails. Sikh, Muslim and Christian communities and social institutions also exhibit caste discrimination.6

One of the greatest difficulties in working with disadvantaged people in India is that they believe they don’t deserve better and so discrimination on the basis of caste permeates all the social structures of India. Even marriage outside of caste is difficult and the dowry (gift) is expected in marriages in most states.

The huge disadvantages facing Dalit girls are related to endemic problems within Indian society and the school system. But the Dalits are not without political leaders who in 2001 invited all religions to educate their children by establishing English medium schools of high quality. In response, the All India Christian Council set a target of 1,000 schools and to date OMIF has contributed 104 to this target.

English medium education is the gateway to tertiary education, but it has been inaccessible to most Dalits. Government schools teach mostly in the local language, but higher caste Indians who can afford private schools have their children educated in English medium schools and support them further with tutoring. Few Dalits have had access to this education. By establishing English medium schools, OMIF is bringing high quality English medium education to Dalits and opening up tertiary education to them.

OMIF schools face the same retention problems that all schools in India face when educating people from disadvantaged backgrounds. In the south, girls outnumber boys at some schools but in the north retaining girls remains a major issue. For success these schools will have to seek much closer cooperation with their communities to break down the prejudice against educating girls and to change the mind set of the parents about the benefits of girls completing school to at least 10th Grade. There was a time in most western countries when there were affirmative action programs to improve the retention of girls. That time has now come to India. Educating girls from only the higher castes will further entrench caste differences, delay the education of girls from disadvantaged communities and continue the disempowerment of women. Programs that support the education of girls from disadvantaged communities must be the priority. In this regard, the 104 schools of OMIF are to be commended and so to the efforts of all those organisations that are targeting girls from disadvantaged communities.

Conclusion

The improved education of girls, especially the education of girls from disadvantaged groups, will change India. As documented in the case of the state of Kerala, educated girls become educated workers, mothers and citizens. They bring unprecedented social and economic changes to their families and communities. Additionally, girl’s education will produce women who demand respect when none is given, who will use their social and political power to change the long embedded customs and beliefs that make the lives of many Indian women one of suffering and discrimination.

References

Basumatary, Rupon; School Dropout across Indian States and UTs: An Econometric Study, International Research Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 1(4), 28-35, December (2012)

Deepa A; Government stalling secondary school reforms

Reforming Government Schools for Girls' Education

Nelson, Dean Delhi swept by protests over child rapes The Hindu 22 April 2013

Mohanraj, Pranati; Understanding Girls’ Absence from School in Madhya Pradesh, India: An Investigation The University of York Women’s Studies 2010

Myers B L 1999, Walking with the poor, Orbis Books, New York

Ramachandran Vilma; Beyond the numbers, Hindu Newspaper 24 Feb 2002; http://www.indiatogether.org/

Sarma Dr EAS A study on the Status and Problems of Tribal Children in AP 21/10/2008; http://www.mynews.in/fullstory.aspx?storyid=11698

Stonne, Lina Searchlight South Asia March 21st, 2012

Wink W Engaging the powers: Discernment and resistance in a world of domination Fortress Press, Minneapolis USA

H. .